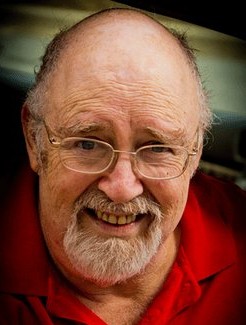

Jon Franklin, winner of two Pulitzer Prizes and an author and teacher who fomented the late-20th century revolution of literary journalism in American newspapers, died Jan. 21 in Annapolis, Maryland. He was 82.

Franklin, a professor emeritus at the University of Maryland’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism and a 1970 UMD alum, died at Hospice of the Chesapeake after a Jan. 8 fall at home, said his wife, writer Lynn Franklin. In the past two years, he had undergone treatment for esophageal cancer.

Franklin, a professor emeritus at the University of Maryland’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism and a 1970 UMD alum, died at Hospice of the Chesapeake after a Jan. 8 fall at home, said his wife, writer Lynn Franklin. In the past two years, he had undergone treatment for esophageal cancer.

From coast to coast for four decades, Jon Franklin’s byline heralded a new path for journalists seeking to create the art of real life. With his landmark 1986 book, “Writing for Story,” Franklin pushed news writers to seize the literary tools of Chekhov and Steinbeck and build “chronologies of meaning” on the foundation of newsgathering.

"Jon Franklin proved to a generation of journalists that good reporting could gain the power of literature," said Roy Peter Clark, nationally renowned author and writing coach at the Poynter Institute in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Writer Adina Gewirtz of Silver Spring, Maryland, a longtime friend of the Franklins, said Franklin “changed my life, and I know I’m not the only one.”

“Jon wanted to be the teacher of a lifetime,” Gewirtz said. “He was passionate about the truth and the power of story to tell it, and he loved his students long after they’d left the classroom. We loved him back.”

In addition to his newspaper work and seven books, Franklin pioneered the internet’s potential for connection. In 1994, Jon and Lynn Franklin established the listserv WriterL, a virtual salon about literary journalism. Over 15 years, WriterL grew into a lively exchange that a New York Times story likened to Paris in the 1920s.

A hard Oklahoma boyhood kept Franklin from pursuing the education to fulfill his dream of becoming a scientist. Instead, he enrolled in what he called the “universal school for writers” — the novels of Fitzgerald and Hemingway, and the short stories in the Saturday Evening Post and other popular magazines of postwar America.

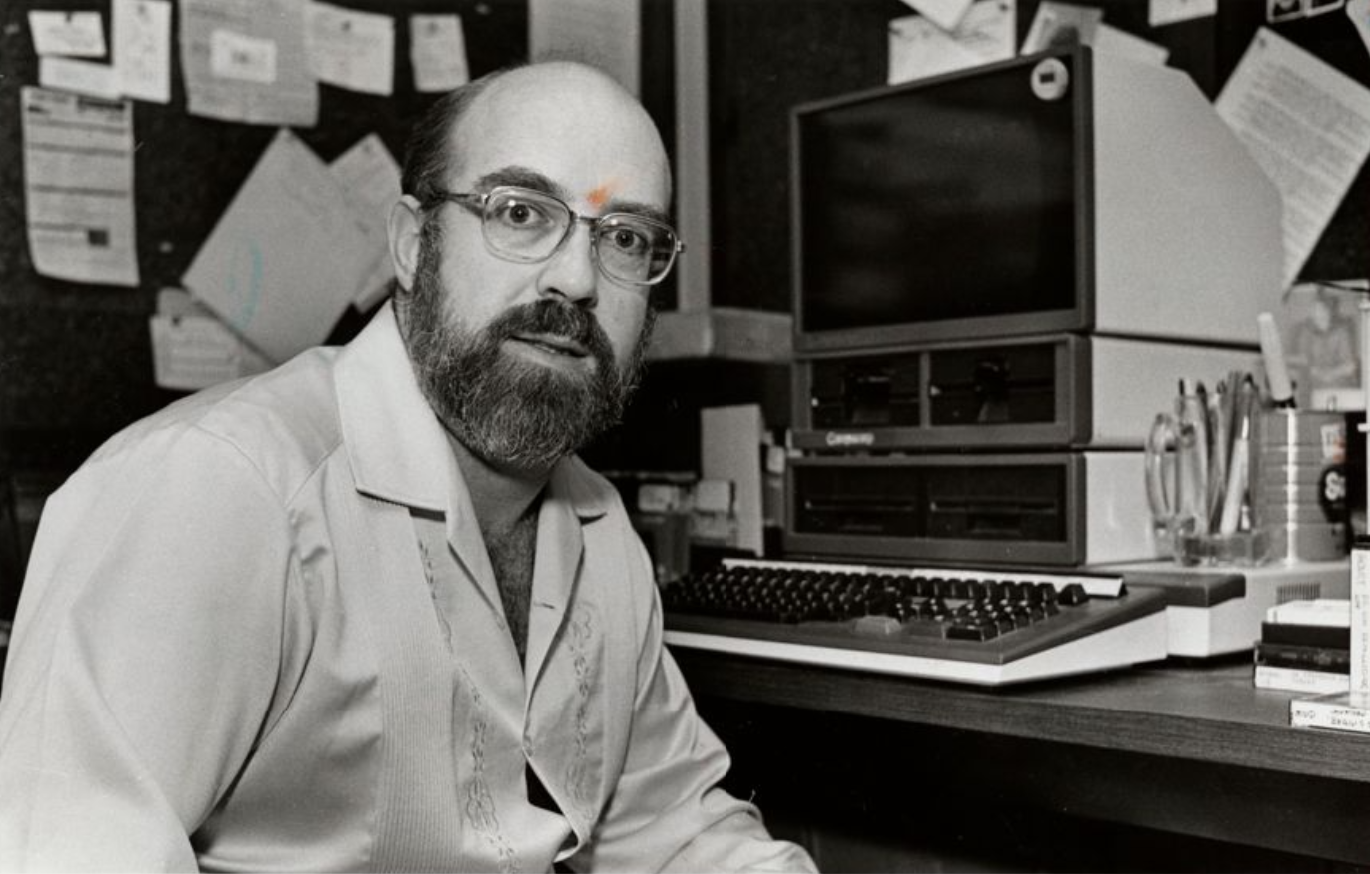

The currents of science and literature carried Franklin to The Baltimore Evening Sun, where the science beat had sat open, ignored. Franklin claimed it and made it into a showcase of reader-pleasing narratives. In 1979, he earned the first Pulitzer Prize awarded for feature writing for “Mrs. Kelly’s Monster,” a story about a brain surgeon and his patient. In 1985, he earned the inaugural Pulitzer for explanatory journalism for “The Mind Fixers,” a seven-part chronicle on the dawn of molecular psychiatry.

Setting the bar in two Pulitzer categories established Franklin as a master of the craft, a sought-after teacher and speaker.

“Jon Franklin fused the modern discipline of journalism with the ancient magic of storytelling to create a new literary genre capable of bridging the gap between the sciences and the humanities that has long divided mainstream culture,” said Seattle writer John Higgins, a Franklin student and friend of three decades.

Franklin then published his definitive how-to book, and its title baldly announced the contents: “Writing for Story: Craft Secrets of Dramatic Nonfiction By a Two-Time Pulitzer Prize Winner.” The book is his best seller and remains in print after nearly 40 years.

Born Jan. 13, 1942, in Enid, Oklahoma, Jon Daniel Franklin was the first son of Wilma and Benjamin Max Franklin, an itinerant construction electrician who picked fights in honky-tonks. But his father encouraged his son’s interest in writing.

Franklin rarely stayed in the same school for more than six weeks as the family moved around for his father’s work. He quit high school to join the Navy. His writing ability got him orders to All Hands magazine, the Navy's glossy journal of profiles and photographs, published at the Pentagon.

With the Vietnam War escalating, Franklin mustered out of the Navy after eight years, and the G.I. Bill allowed him to be the first in his family to go to college. He earned a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Maryland in 1970. He wrote first for The Prince George’s Post then for The Baltimore Evening Sun.

After his second Pulitzer Prize, he moved into the classroom, first at what was then Towson State University, then at UMBC, then his alma mater (now Merrill College) where he became a full professor.

"It's a hard road for people who are trying to write the true literature of what's happening in society," he told College Park magazine in 2001. "Are rock stars really our heroes? I don't think so. They have their place, but they shouldn't be the big story. The main event is life, and that's the principle I want to make sure students are exposed to."

In Baltimore, Franklin met Lynn Scheidhauer, a writer at a local college, and they married in 1988. The next year, the Franklins went west for Jon to head the journalism program at Oregon State University. Later, he went to the University of Oregon to teach journalism and serve as director of creative writing.

In 1998, Franklin was lured back into the newsroom. He and Lynn left Oregon for North Carolina, where Jon became science writer for The News & Observer in Raleigh.

The Franklins aimed to retire in North Carolina with a succession of black standard poodles. But in 2001, the University of Maryland offered Jon Franklin an endowed position, the first Merrill Chair in Journalism. The Franklins moved once more, to a house in the pine woods of Sunderland, Maryland, just west of the Chesapeake Bay.

Even after his retirement from the University of Maryland in 2010, Franklin coached writers. In 2019, the Franklins moved to Annapolis. At his death, Jon Franklin was working on a memoir of his Oklahoma boyhood.

Franklin received honorary degrees from the University of Maryland in 1981 and Notre Dame de Namur University in 1982. In 1985, the American Chemical Society bestowed on Franklin its James T. Grady Award, once given to Isaac Asimov. In 1986, Franklin was a semifinalist in NASA’s Journalist In Space program. In 2005, he was inducted into the UMD Alumni Hall of Fame.

Survivors include his wife of 43 years, Lynn Franklin, of Annapolis, his daughter Catherine Franklin Abzug, and her husband Morty Abzug. Franklin’s parents and younger brother Douglas predeceased him.

Funeral arrangements are pending. Contributions in Jon Franklin’s name may be made to Hospice of the Chesapeake, Annapolis, Maryland.

If you would like to share memories of Jon Franklin to include on this memorial page, email them to Merrill College Communications Manager Josh Land (joshland@umd.edu).

In addition to “Writing for Story,” Franklin also wrote:

- “Guinea Pig Doctors: The Drama of Medical Research Through Self-Experimentation,” in 1984 with Dr. John Sunderland.

- “Shocktrauma: The Dramatic True Story of a Pioneering Hospital Team to Conquer the Most Lethal Killer of All,” with Alan Doelp, a 1985 work of dramatic nonfiction that was turned into a Canadian television film.

- “Not Quite A Miracle: Brain Surgeons and Their Patients on the Frontier of Medicine” in 1983, also with Doelp.

- “Molecules of the Mind: The Story of the Psychological Discovery that Changed the World,” a New York Times Notable Book of the Year in 1987.

- "The Wolf in the Parlor: The Eternal Connection between Humans and Dogs" in 2000.

- "A Place Called WriterL: Where the Conversation Was Always About Literary Journalism," in 2022, with Lynn Franklin and Stuart Warner.

Jon's work was the "gold standard" for those of us who write about health and science. When I taught feature writing and science writing at Merrill, I used "Mrs. Kelly's Monster" as a centerpiece for both courses. It was brilliant (also a little flawed), and, for those reasons, a powerful teaching tool. He came and spoke to my classes about it.

Jon told me several times that he regarded every piece he wrote as "practice."

Well, he mastered his craft, since just about everything he wrote was near perfection.

Marlene Cimons (Ph.D. '08)

Washington Post contributing reporter

Everything I know about writing I owe to Jon, who was my professor, my mentor, my confidant, my friend. I still hear his voice in my head when I write, though it's been more than 30 years since I sat in his classroom. I feel him pushing me to outline my stories, to use active verbs, to boil everything down to three words. He was there for me long past my time at J-school. He listened to me for hours on end as I struggled to figure out who I wanted to be. Not just as a writer, but as a person. He helped me through my first divorce. He delighted in my successes. Told me how tickled he was to see me grow. Jon was an outstanding human, an extraordinary writer and thinker. He demanded a lot of his students but he gave so much more. The last time I saw him, I took him to lunch on my way to a reunion in Annapolis. I was happy to be able to do something nice for him for once. He will be sorely missed, but his influence will live on forever.

Laura Williamson

LWM Communications

I am sorry to hear of Jon’s passing. He taught a very memorable Science and Journalism course that met for 2.5 hours once a week. It followed a beautiful arc, from humanity trying to understand the heavens and its most far-flung stars to the endless investigations of our closest molecules, our minds and ourselves. Jon challenged us, and did not shy away from prolonged, thoughtful silences in pursuit of rich dialogue.

He used to say that when he was working on a solution to a particular problem, he would isolate the question he was trying to answer while falling asleep, and oftentimes the answers would arrive in the morning. Jon was probably one of the most thoughtful people I’ve met. You could call it obsessive, but it wasn’t that. He was utilizing his mind with the understanding that each day offers an opportunity to grow and deepen our grasp of the world and our place in it.

Christian Kloc

2010 Merrill College alum